Unpacking Community (Part 1)

Ancient Understandings

These days, when I talk about community, I get a variety of responses. Some give me blank looks and say things like, “Well, we do too many things already,” as if community was about a quantity of activities. Others want the quantity of activities but not the times where we just sit and talk. I want to take these people to the East, where we just sit, talk, and drink tea.

I really can’t blame people for not connecting with my quest for community. After all, I’m a single guy in Lancaster County with few deep communal roots and few cousins nearby. Maybe my friends already have community among their extended families and decade-old friendships. Maybe I need to work harder to put down roots in the expensive Lancaster County soil. Or maybe I shouldn’t be overly concerned with the roots of vocation, extended family, land, and money. Instead, maybe I should dig deep into the foundations of community and unearth treasures that I can take anywhere. So, here is the start of my dig.

Community, Koinonia, and the Early Church

When we talk about community, it is important to define what we are talking about. It is also helpful to phrase important discussions in Biblical terms. Because of these reasons, I will define and explore community by digging all the way back to the ancient Greek word koinonia, which is often translated fellowship in the New Testament. In this post, I will use the words community and koinonia interchangeably.

Koinonia means participation, distribution, communication, communion, and intimacy. It is an important word, as the apostle John tells us he wrote his first letter to bring us into koinonia with other Christians and the Godhead (1 John 1:3). On an external level, koinonia involves participation. In strong communities, people live, work, laugh, cry, and worship together.

Koinonia also involves distribution. When there is a need, community members distribute their surplus money, possessions, time, and energy. Many groups have practiced this in informal, spontaneous ways. Other groups such as the Hutterites practiced this in formal, structured ways. In these radical koinonias, everyone relinquished all their personal property to the group, which then provided for the welfare of its members and distributed money as there was need.

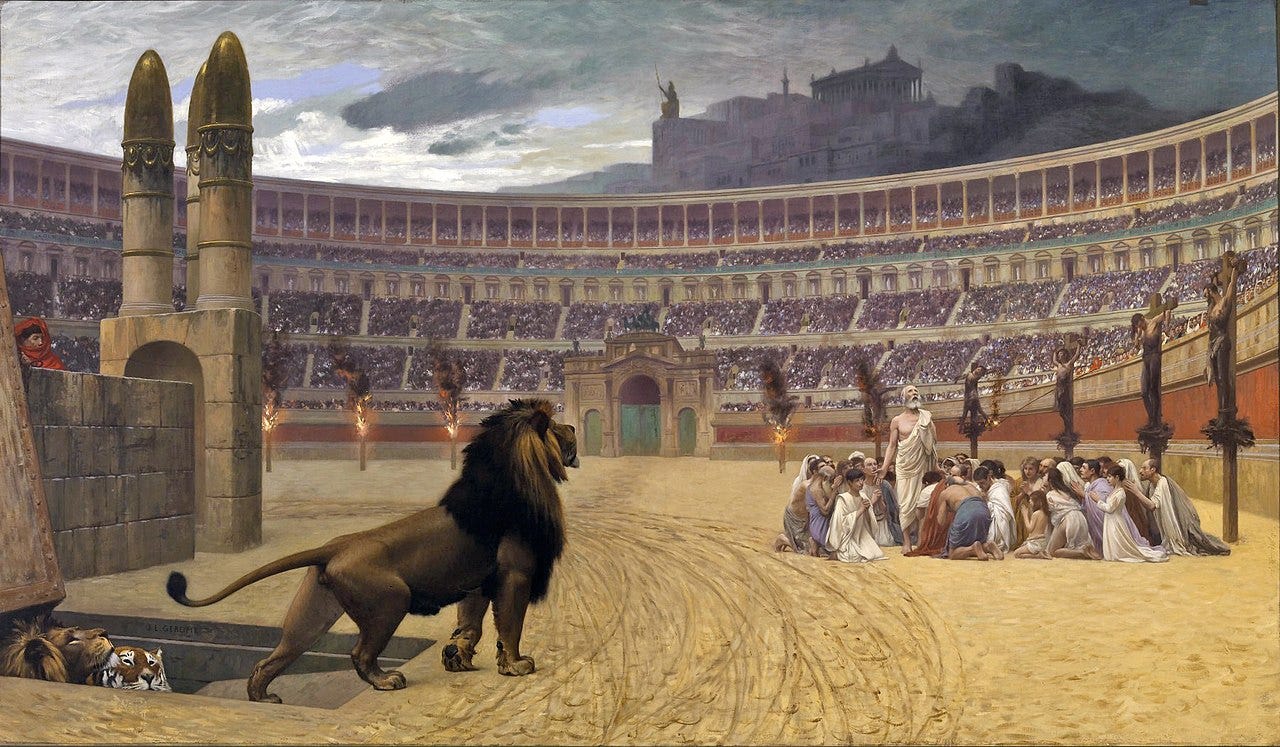

We especially see participation and distribution in the early Christian koinonia, where its members regularly ate together, distributed their possessions to everyone who had need, and worshiped in the temple. Acts 2:42 says that the disciples continued steadfastly in koinonia. In Romans 15:26, the saints in Macedonia and Achaia collected money as a koinonia for the poor saints in Jerusalem.

For strong koinonias to work, there must be plenty of communication. On a personal level, there needs to be good questions and active listening. On a group level, there should be deep discussions and teaching. You will know there is good communication when you hear positive talk in many places—interesting talk, deep talk, light talk, loving talk, and hard talk—interspersed with good bouts silence, of course.

On a deeper level, koinonia involves intimacy, which is a deep connection between hearts that includes commitment, feelings, and actions. While intimacy is invisible, it does express itself in many visible ways. And it is something that cannot be easily measured or forced. Whenever community becomes involuntary, intimacy suffers. And without intimacy, community is superficial and could even be hurtful.

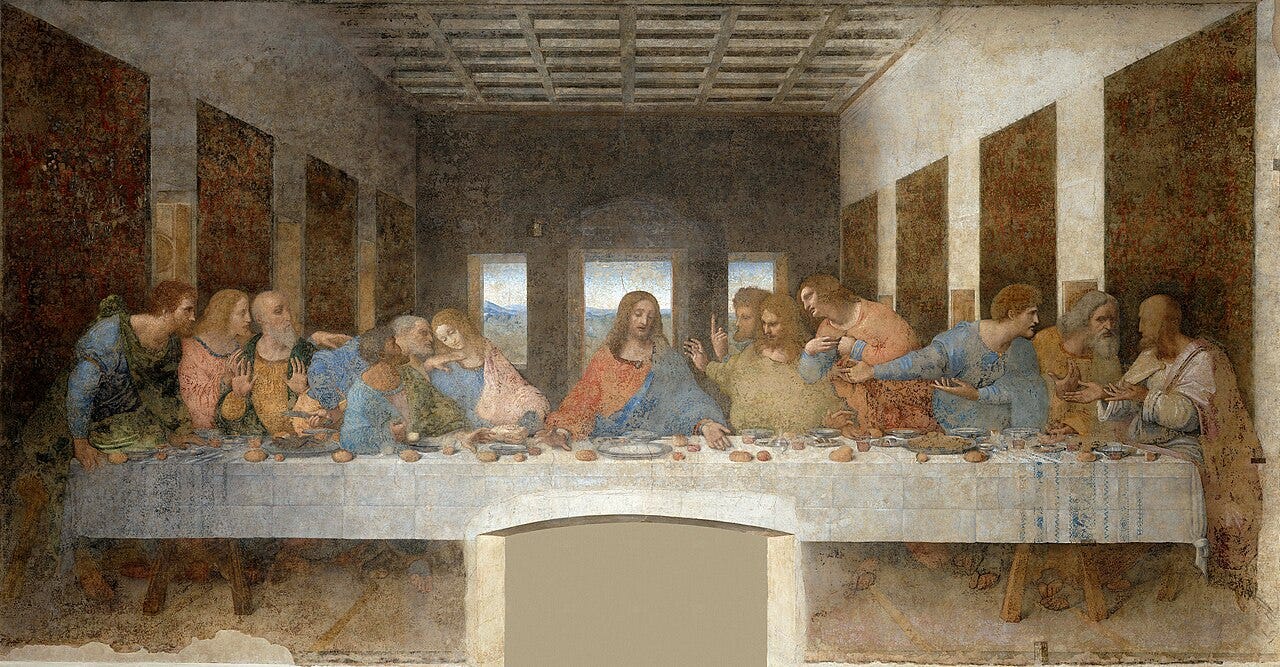

Koinonia and the Eucharist

Any discussion of New Testament koinonia would be deficient without a mention of the Eucharist, [1] which expresses koinonia in important ways. In this important sacrament, the words of Christ are communicated to the participants. Then, the bread and the wine are distributed equally to all members of the spiritual community, whether male or female, rich or impoverished, educated or mentally disabled. As the diverse participants eat the break and drink the wine, their hearts and souls are knit together and united with the passion of Christ. They enter the koinonia of Christ’s sufferings (Philippians 3:10) and are made one in Him.

But not only does the Eucharist express koinonia, it is koinonia. 1 Corinthians 10:16 says that the cup and the bread is the koinonia of the body and blood of Christ. Those who participate in the bread and wine enter a deep experience of community, not just with each other, but also with Christ. One Anabaptist thinker puts it this way: “Liturgical, worshipful practices [the Lord’s supper] are not mere symbols or ceremonies. They involve fellowship, participation, and partnership with the beings we worship.” [2]

Naturally, the Eucharist was a regular part of the early church, a central part of their koinonia. One could even make the argument that it was their koinonia, from which other parts of their community flowed. And while the Eucharist has been debated over the centuries since, it has continued as an important practice in all orthodox Christian churches. A contemporary Anglican writes the following:

The Lord’s table is the place where heaven and earth is being reunited now, where koinonia in Christ is created and renewed, where intimate and mutual indwelling happens on earth as it is in heaven. Let us therefore keep the feast! [3]

Koinonia and Aristotle

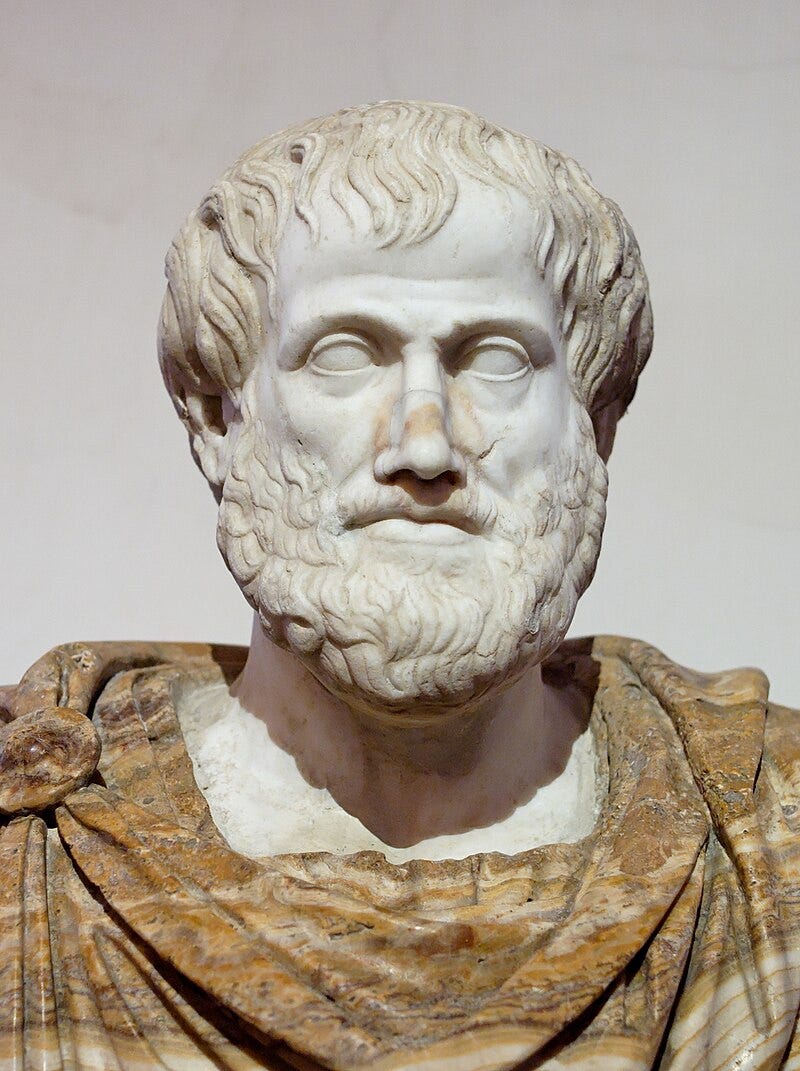

Interestingly, the influential Greek philosopher Aristotle wrote about koinonia before the time of Christ, and I think it is no coincidence that the New Testament writers also used this word. As they wrote about koinonia, they would have at least partly understood the Greek context and worldview of their Greek readers. By studying how Aristotle used koinonia, hopefully we can better understand the context of early Christian koinonia.

As an introduction to Aristotle, he was the man who tutored Alexander the Great, wrote hundreds of books, produced the earliest known formal study of logic, and developed a natural philosophy that shaped the history of science. He was especially influential on medieval thinkers, being revered by both Christians and Muslims of that era.

In Aristotle’s work Politics, he outlines a vision for a flourishing society. In it, he calls various communities koinonia, from the single family to the polis, known as the city or republic in English. Aristotle had observed that humans naturally form communities, and he attempted to convey both the reason the communities formed and the purpose of their existence. Commenting on Aristotle’s writings, one modern writer says this: “People form a koinonia when they individually want or need something, and they cannot possibly, or cannot easily, procure it as individuals working independently, yet they can do so if they cooperate.” [4]

Aristotle believed that the public life was more virtuous than the private life and that the polis, or Greek republic, was the highest form of koinonia. And while the purpose of the private koinonia was to provide for basic needs, the purpose of public koinonia, or the polis, was for a loftier goal. While the polis needed justice and economic partnership to enable people to live together, the ultimate goal was to foster an environment for people to live a good life. In his view, the polis existed so its citizens could perform beautiful, noble actions.

The New Koinonia

When the writers of the New Testament talked about a new koinonia, they were subverting many other koinonias, especially the polis. The new Christian koinonia required absolute commitment, even above the family koinonia and polis koinonia. The simple, yet radical ways of the new koinonia disrupted the current world order. While it was based on theology and the simple teachings of Jesus, it began to reshape the political, economic, and social constructs of its day. While many early Christians were able to stay within their existing koinonias, many others needed to discard their loyalties to their families and republics. No wonder the polis, now Roman, felt threatened.

The Greek context of koinonia is also important because it the early Christian koinonia had many similarities to the Greek koinonia. As Aristotle taught, the purpose of koinonia is not simply to help each other survive; rather, it is to enable noble actions and beautiful flourishing. This is also the purpose of the Christian koinonia, to welcome the flourishing Kingdom of God.

Also, koinonia is an essential part of our existence. Aristotle writes, “One who is incapable of sharing (koinonien) or who is in need of nothing through being self-sufficient is no part of a city, and so is either beast or a god.” [5] In a similar way, the Christian who claims to be self-sufficient and refuses the help of others is not living as a new person in Christ and is not part of the new koinonia.

So, I guess I am pursuing community, not only because I lack solid earthly roots, but also because koinonia is an essential part of human heart and history. And, as 1 John tells us, God wants us to have koinonia with Him. I believe that this is not only because God wants our good but also because he really wants us. But that is getting into the topic of the next post.

[1] I use the term Eucharist for the Lord’s Supper because it is the early Christian term found in the Didache, one of their earliest extra-Biblical texts. I also appreciate the meaning of the word Eucharist, which is thanksgiving.

[2] Sommers, Marlin. https://anabaptistperspectives.org/essays/the-lords-supper-as-fellowship. Accessed 08/17/2024.

[3] Borah, Fr Chris. https://ctkbeckley.com/2022/05/10/koinonia-the-movement-of-the-eucharist/. Accessed 08/17/2024.

[4] Pakaluk, M. (2005). Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics: An Introduction. (n.p.): Cambridge University Press. p. 271

[5] Aristotle. Politics. 1253a28-30

Thanks for sharing.

I like the way you explained the need for community

But what really stood out to me was how God not only wants our things but wants us.

May God bless you as you keep writing